Listen the podcast

You may have heard time and again about how people use only ten percent of their brain; and you also may have wondered what if our brain could fulfill its potential.

If we managed to develop the remaining 90 %, we could certainly levitate, walk on fire without getting burned, or perhaps we could even walk through walls.

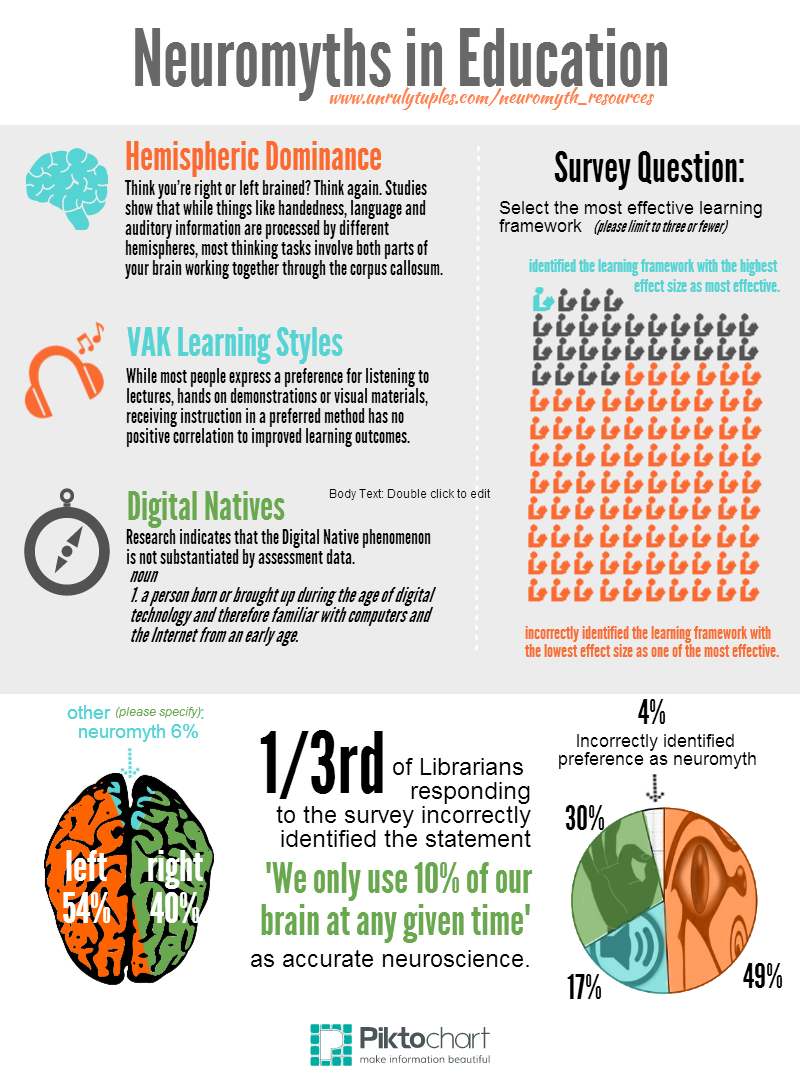

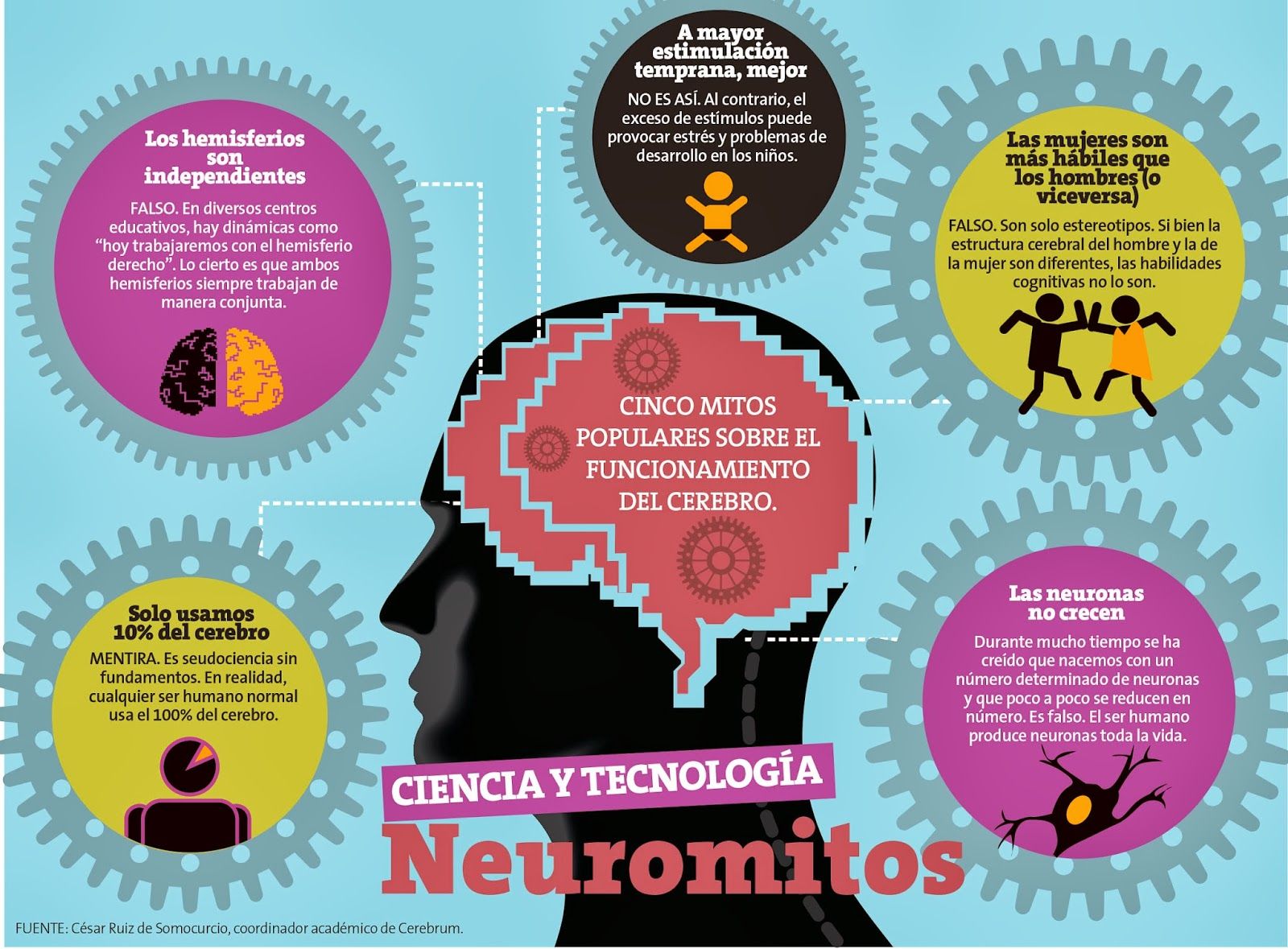

However, the 10 % of brain is, in fact, a commonplace myth around the world without any scientific evidence. This misconception, and many others, is widespread among the general public and can impact negatively students’ academic success.

If we believe that boys are good at mathematics and girls are not, why, then, do we have girls take the trouble to learn it? If the brain does not change and if our mind is predetermined by genes, it is better to let things take their course, the advanced students will be successful , and the less advanced ... well, that’s their problem!

Despite the fields misconceptions cover, the worst of it is that they serve as a cognitive justification for our behavior. Eventually, we may get discouraged to go into action, when we believe in something that seems impossible to change.

Within the field of neurosciences, the misconceptions about the brain functioning and cognition, are called "neuromyths".

Elena Pasquinelli, Professor and researcher at the Department of Cognitive Studies at the École Normale Supérieure de Paris, has been studying neuromyths for quite a long time. According to her, the causes of neuromyths are countless; these causes may be scientific facts that have been distorted.

For example, a newspaper or magazine can publish a story with a headline announcing that "the gene for love" was just discovered. The aim of the newspaper is to attract the attention of an audience. But, the headline is an oversimplification of the original research result. Although the objective is achieved, the headline is far from the truth.

Neuromyths can also be the result of scientific hypotheses that have been confirmed for a period of time, but, due to the accumulation of new evidence, those hypotheses were disproved later on. As the new evidence take time until it reaches the public, we continue to function with an outdated knowledge that we still consider relevant.

This is the case for the so-called "Mozart Effect".

In 1993, Frances Rauscher, Gordon Shaw and Catherine Ky, investigated the effect of listening to Mozart's music on spatial reasoning or the ability to manipulate two and three-dimensional elements.

Their initial research results, published in the prestigious journal Nature, reported only a temporary increase in spatial reasoning skills, that lasted about 15 minutes. And a subscale of the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Test was used to assess reasoning skills before and after listening to Mozart’s music.

However, the phrase "increase in intelligence" was popularly misinterpreted when the results were published by the large media outlets, including the New York Times and the Boston Globe.

Recent studies have verified a different reality. According to the new evidence, Mozart's music does not increase performance in some cognitive skills, it is rather the exposure to an enjoyable melody, or any other sound stimulus, what makes the difference. This phenomenon is called "enjoyment arousal". But, any increase in cognitive functioning is very small and temporary.

So, it is music what can have a small, temporary, positive effect on some of our cognitive processes. it may be Mozart’s, Metallica’s or any other kind of music you enjoy listening to.

Dr. Pasquinelli also suggests that the appearance of neuromyths may be caused by a wrong interpretation of scientific results. Let's refer an example proposed by Dr. Pasquinelli about the myth of the first three years, which are believed to be a crucial time for learning.

This myth is supported by an approach holding that learning depends exclusively on synaptic growth, that is, on the increase in the connections between neurons in our brain, which is totally unsupported.

Although our neurons connectivity increases in an extraordinary way, during the first three years of life, the supporters of this myth do not take into account that the brain plasticity processes are the result of the interaction of the brain anatomy and functioning with the environment, as an external factor. Learning not only depend on the brain structure itself, but it also depends on the environmental and social influence.

Neurophilia, or our fondness for brain topics, becomes fertile ground for a score of myths. In other words, due to our growing appetite for brain-related news, whenever the term neuro is used, even in some scientific disciplines, it automatically increases the relevance attributed to the information that is delivered.

Neuromyths are not as harmful to our daily lives as false information, no matter where it comes from or what field it refers to. That’s why, we suggest you to delve into all the information about the brain that you consume.

There’s a whole lot more to discuss about neuromyths We will continue telling you about them in upcoming podcasts.

And to round off this discussion, we’ll take the liberty of asking you a question: are you now knowledgeable about the brain or are you likely to fall under the spell of neuromyths yourself?

Would you like to know?

In case you are interested, you can put yourself to test. Here’s a survey (english survey and spanish survey) you need to complete by writing true, false or I don't know in order to answer the questionnaire.

In the questionnaire you will find questions about the 10% of brain myth.

In case you believed in it before listening this podcast, we hope you’ll answer honestly. After all, isn’t getting to know us better what this is all about?

Summit your replies as soon as possible. You will be able to verify your answers when you complete the survey

We hope you enjoyed our program.

Remember that you can and subscribe to the page! Download the podcast and share it with friends