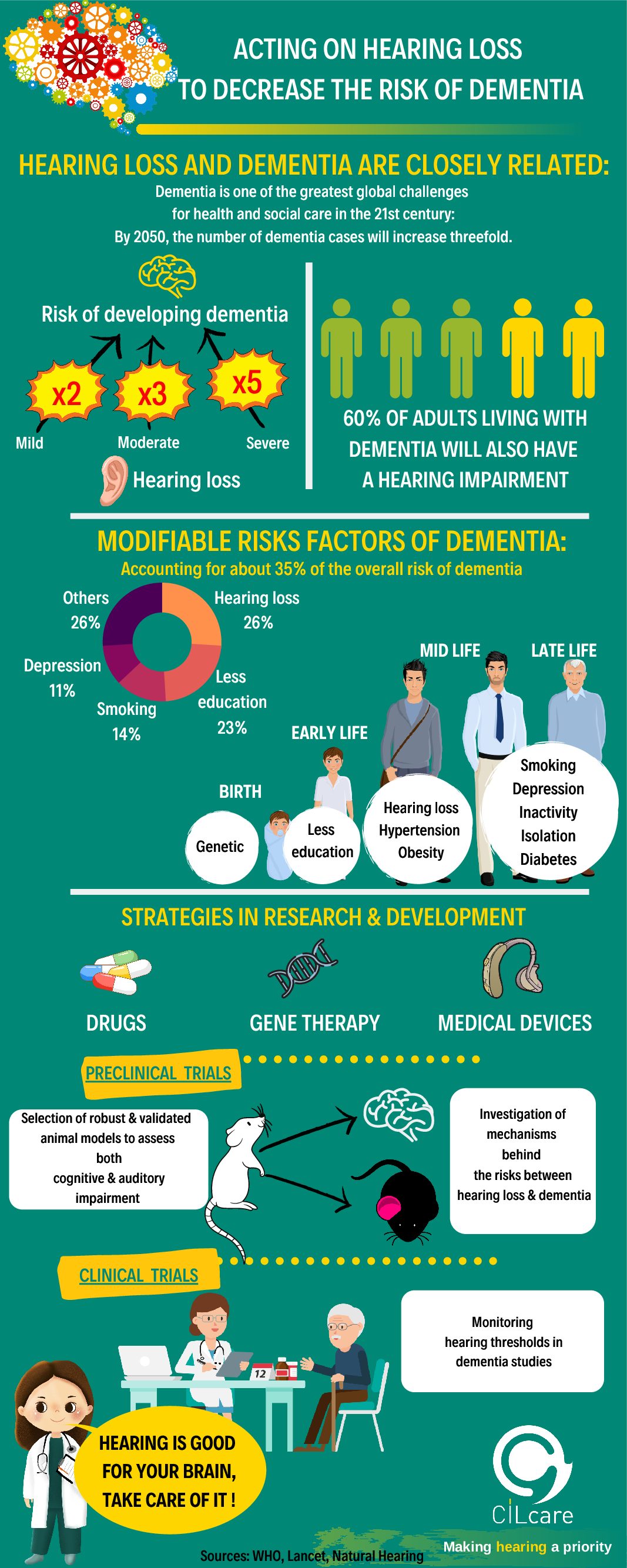

In a previous post, we discussed about how we could reduce the risks of developing dementia. And we also mentioned the twelve modifiable risk factors, which are altogether responsible for approximately 40 % of all dementia cases around the world.

Low educational level, high blood pressure, obesity, smoking, physical inactivity, social isolation, the presence of depression, air pollution, traumatic brain injuries, excessive alcohol consumption, diabetes and hearing loss.

In response to your suggestions, today we discuss about the relation between hearing difficulties and dementia. The rest of the risk factors will be coming soon.

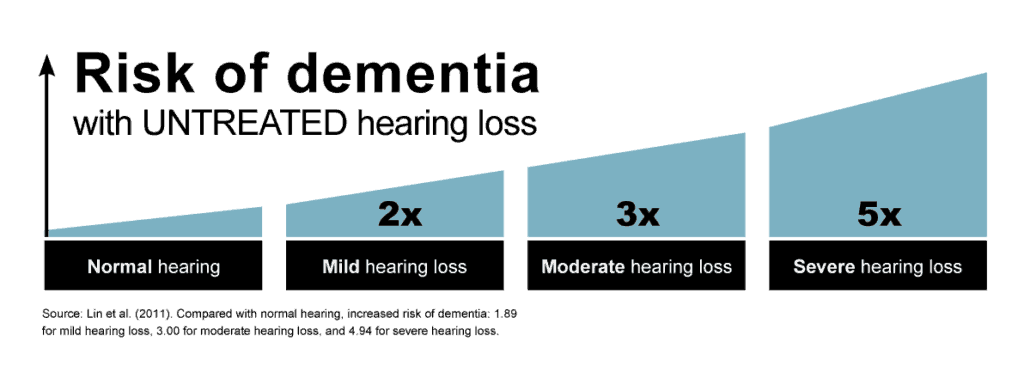

According to the most recent study, published by the Lancet commission, hearing loss is a major risk factor for the development of dementia, with an 8% of the cases, especially during middle adulthood, from 45 to 65 years of age.

This figure is much higher than other risk factors at the same stage of life, such as traumatic brain injuries 3%, hypertension 2%, alcohol consumption and obesity, both representing 1 %.

Other studies suggest that a dementia risk increases 1.3 times for every 10 decibels of hearing loss. It has been proved that even people who do not have a pathological hearing deficit, a hearing loss greater than 25 decibels according to the WHO, could also present a decrease in their cognitive functions.

According to the WHO, when patients have a hearing loss higher than 25 decibels, they are considered to present a pathological hearing deficit. However, it has been proved that even people with a hearing loss below 25 decibels, say, for instance 10 decibels, could present a decrease in their cognitive functions as well.

But how is hearing loss related to dementia?

When we think of losing our hearing ability, we immediately, and almost intuitively, associate it with dementia. This is because our social life begins to be limited, and consequently, we find it difficult to communicate, exchange opinions with relatives and friends.

As our social contacts decrease, we tend to isolate ourselves from the rest of society. This situation may also increase the risk of suffering from depression. So, both social isolation and depression, two main risk factors, can obviously increase the incidence of developing dementia.

In this sense, hearing loss can become a condition that would amplify the vulnerability for the appearance of other risk factors that also impact negatively our cognitive and brain health.

Is this the only mechanism?

Well, absolute not. The most recent study of this issue was carried out by Dr. Jeremy C. S. Johnson, lead author and professor at the University College London, and his colleagues.

Apparently the mechanism that links hearing loss with the development of neurodegenerative processes is more complex than it appears at first sight. Dr. Jeremy C. S. Johnson and his colleagues proposed a new perspective in their article "Hearing and dementia: from ears to brain" published in the journal Brain.

They refer that the neurodegenerative processes, the distinctive feature of dementias, affect the brain auditory circuits in a particular way

In other words, the brain is our main organ of hearing.

Dr. Johnson also states that "listening" seems simple, but it is actually the result of complex brain circuits, that allow acoustic signals to be converted into mental representations. it means that sound, the physical stimulus, is represented in our brain thanks to the connectivity between neurons or synapses.

Anatomically, in our brain there are highly specialized circuits to process sounds, and these circuits are widely distributed throughout the cerebral cortex.On the other hand, proteins associated with neurodegenerative processes show, so to speak, a propensity to undermine the structure of those circuits, which significantly affects our ability to process sounds.

Another interesting fact is that hearing impairments in dementia patients are not homogeneous, but show unique characteristics depending on the type of neurodegenerative pathology.

Alzheimer's disease patients usually present sound agnosia, which is the inability to identify the origin of sounds, or to relate the sound to its source, for example, patients cannot associate barks with a dog; and they also show increased sensitivity to acoustic stimuli.

These manifestations have been related to the neurodegeneration of brain circuits of the temporo-parietal cortex.

On the other hand, a different pattern is observed in patients with frontotemporal dementia, which is a type of dementia that differs from the one caused by Alzheimer's; patients are not able to identify environmental sounds and people's accent.

Additionally, they present word deafness, that is, they are unable to understand language, repeat words or write when dictated. These difficulties are related to atrophy of the prefrontal lobes, unlike what Alzheimer's disease can cause to them.

Why are these features important?

These profiles of auditory degeneration or auditory phenotypes, not only indicate the existence of damage to the brain circuits, which participate in acoustic processing, but they also are of great help to determine the type of neurodegenerative process a patient presents. In this case, they become a marker that helps us differentiate the several types of dementia.

So, are hearing difficulties a cause or a result of dementia?

This is a tough question, but little is known about this interaction. However, there are some results suggesting that hearing difficulties can be a clinical signal of a pathological brain process. Therefore, if hearing disorders are not treated in due course, they can become a factor that accelerate the degeneration of the brain cells.

One thing leads to another. At this point, we all agree on the importance of making a positive assessment of any manifestation of hearing loss that any relative, friend or we may be experiencing.

Nowadays, there are intervention alternatives that allow the management of hearing loss, ranging from the use of devices to medications and surgical interventions. But this would already be the subject for another podcast.

In case you want us to deal with a specific topic, please, leave your suggestions in the comments section.

And remember, you can also download our pocast (in Spanish and English).